An Ode to the United States: On the (Proposed) Sinking of America's Great Flagship

- Drew Maglio

- Mar 8

- 17 min read

Updated: Mar 11

It wasn’t supposed to end this way for America’s flagship: i.e., the SS United States: the ship bestowed with the honor of bearing the namesake of her nation; she is, perhaps, the greatest merchant ship to ever be constructed by, and operated under, the American flag. If you haven’t been following the news, the SS United States was towed by tug from Philadelphia to Mobile, Alabama this past week; at many points along the route, the great liner was visible from shore, and remarkable images of her ghostly condition, beautiful sleek lines, and otherwise bygone aura, have been circulating on social media. As of Monday, the “Big U,” as she was affectionately called, has been moored to what will in all likelihood be her final berth in Mobile, Alabama, where she will be drained of her fuel-oil — and stripped of all other environmentally-toxic chemicals and pollutants — in order to make the great ship safe for her scuttling off the coast of Okaloosa County, Florida (Destin) in 2026: what a sad, sad end for a twentieth century American icon!

The Present Situation

These happenings have occurred concomitantly with the second restoration and reopening of the RMS Queen Mary Museum — Britain’s great (interwar and post-war) flagship, who has recently been restored again, and now rests heartily in Long Beach, California; Such a thing feels to me, an American, as a bastardization of justice: for the SS United States was perhaps, technologically speaking, the greatest ocean liner of all time: the final form of an evolutionary development that was a bit too late to be fully appreciated; the Big U is much like an Iowa-class battleship — of which all four are preserved — in this regard: incomprehensibly powerful and effective at fulfilling a somewhat obsolete design ethic, but remarkably majestic nonetheless. Unlike the Iowas, however, the United States showed what mid-twentieth century American industry and engineering could accomplish in a peacetime, civilian capacity.

Tragically, she will soon languish in serene solitude, forever out of view (as she has been for some time), at the bottom of the Gulf of Mexico. Of course, such a glancing comparison (as the one made above) does not appreciate that the Queen Mary was saved at a time when the age of the ocean liner had only recently subsided (1967); consequently, nostalgia and appreciation for man’s final triumph over the sea, made tangibly manifest via the trans-oceanic “superliner,” — which not only moved tens of millions of travelers and immigrants all over the globe over the course of the first six decades1 of the twentieth century, but also deployed and ferried home, millions of the free world’s troops during both World Wars — was much more relevant and intelligible (on a personal level) than it is today; I am, however, heartened by what I perceive to be a great upwelling of public support and sentiment for the ship’s preservation as a museum in Brooklyn, NY — where free, indefinite dockage has been secured.

The Impact of an Icon Cannot Be Quantifiably Measured

When we don’t appreciate or dedicate time to understand the past, we lose sight of historical reality and ourselves: for we are a continuation of the past — we remain a continuity of our ancestors, however fragmentary and broken that dissolving link may now be. As such, there are many armchair critics who believe the SS United States is simply the rusting hulk of a mid-century cruise ship — who fail to understand and appreciate both the technological and socio-cultural significance of the former, “ship of state”2 ocean liner; and the simple rattling off of impressive facts about the Big U’s size, speed, fire-proofing, and all-aluminum superstructure do little to convey her true impact: an impact that waned as time went on, no doubt, but one that flowed from a place of great hope and excitement — conviction and common purpose — when she was christened before a crowd of approximately 30,000 spectators (and approximately 500,000 people, including television viewers).3

To put it succinctly, the SS United States was the last superliner to be conceived and executed while the age of the liner and seagoing transportation — though waning — was still under the light of day: the same cannot be said of the SS France, a great liner in her own right who served a long and dignified career. Modern people, who live in the generic jet-age of standardized plane models and procedures, unpleasant and cramped quarters — and a generalized sense that the adventure begins upon arrival — have much difficulty in appreciating what ocean-bound travel on the great liners of the past century was like. For the purpose of understanding the camaraderie and atmosphere — even magic — of shipboard travel in a bygone age, I cannot recommend enough, The Only Way to Cross, by John Maxtone-Graham.

One of the vital social functions that ships like the SS United States served was the bringing together from all walks of life, disparate people — which had the particular function of humanizing dignitaries, celebrities, and executive officers like the captain. On a ship, all passengers are functionally equal, no matter how much they had paid for their lodgings and shipboard amenities: i.e. all are subject to the captain’s orders and command. Thus, it was not uncommon for regular, hard-working professionals on holiday to meet and mingle with celebrities like Sinatra, Marilyn Monroe, Bob Hope, John Wayne, Joan Crawford, and JFK (before becoming president) — even presidents Harry Truman and Dwight Eisenhower traveled on the SS United States, and frequently mingled with their subjects! Thus, the atmosphere of an ocean liner was far different than that of modern modes of travel and transportation: the whole passage inadvertently became an experience unto itself, imprinting itself on the memory of those who sailed on her (much like a military flag ship).

Conceiving the SS United States as the Capstone of Liner Historical Development

Conceiving of and contextualizing, the SS United States as America’s sole “superliner” requires an understanding of the difficulty that the North Atlantic presented to Western Man for centuries — truly hearkening to the first Europeans who stumbled across this “New World” by way of sailing ship: before the airplane, the only means of transport to worlds oceans away was by ship: first through sail — which lasted many centuries and spanned dozens of generations of sailing ship; then through the bastard-marriage of paddle-wheel steamer to composite sailing ship.4 But by the mid-19th century — with the advent of the steam engine (which spurred an industrial revolution) — things were rapidly changing. When the screw propeller and reciprocating steam engine were eventually invented, ships began to grow exponentially in size, speed, tonnage, and safety in ways deemed hitherto unimaginable.

And yet, almost a century after the launch of the levianthic, SS Great Eastern — a failed, 692’ behemoth powered by steam and iron, that represented a radical concept at the time — the SS United States may very well have perfected the form of the ocean liner. That is to say, she featured the proper combination of not only grace, beauty, and comfortable appointments, but also a level of size, speed, and safety that had never been married so perfectly before. For instance, she was the first ship that had finally solved the age-old problem of fire at sea; of note: it was fire that took the SS Normandie when she was still in the luster of youth. Unlike the ships that had come before, the SS United States’s interior was furnished with compartmentalized spaces featuring fully flame-retardant materials (and heaps of heat-insulating and fire-blockading asbestos); even the RMS Queen Mary, despite her nearly-impeccable record, cannot say such a thing about her construction methodology and materials; and it was fire — however dubious the circumstances — which consumed the latter’s (slightly-superior and more modern) sister ship: RMS Queen Elizabeth. Suffice it to say, the Big U was second-to-none in all of the most significant ways a liner could be measured i.e. safety, speed, affordability, and passenger comfort; if those were her only virtues, such as great ship would be worthy of preservation, but there is more.

The story of the SS United States began during World War II, when the USA realized the dearth of large ocean liners at its disposal for moving troops. Off the top of my head, I can really only think of one substantial liner used as a troop ship by the US Navy: the USS West Point, i.e. the SS America.5 Another (military troop ship) was going to be made of the SS Normandie, but alas it was not to be, as the Normandie — then the greatest and most lavish liner ever conceived and executed — caught on fire,6 whilst being outfit and repatriated as American troopship USS Lafayette, in New York Harbor. Because of the ongoing war — which had taken the nation of France off the world stage (except as a Nazi satellite and buffer state) — the loss of the SS Normandie wasn’t fully felt or appreciated at the time.

SS Normandie: “Ship of Light” and a Floating Art Deco Masterpiece

“Ships of State”: A Nation Without Liners is a Nation Without Troopships

As a result, America had to rely heavily on British shipping, — notably the RMS Queen Mary, RMS Queen Elizabeth, and RMS Aquitania — slow military transports, and military capital ships to deploy and retrieve its troops across the globe. Thus, the United States government saw the merit in subsidizing a truly world-class liner (like the British government had done for decades through the “Board of Trade,” starting with RMS Mauretania and Lusitania), which could be requisitioned as a troop ship by government decree if the need ever arose (it didn’t); hence, the SS United States was born in 1946 — at least in ideation.

The privilege of designing the new ship was given to legendary American ship designer, William Francis Gibbs, who had previously designed many ships for the United States Lines, including the USL’s (at the time) current flagship, SS America. Though similar in appearance, the SS United States is a far cry from a simple upsize of the SS America; rather, the Big U is an evolutionary leap beyond the America’s design, which took the latter’s compartmentalization and fire safety standards even further, and married it to world-class engineering in terms of size, speed, and exotic materials.7

Resultantly, the Big U was lovingly and painstakingly conceived and executed at the behest of Gibbs; the ship became his ultimate creative act and endeavor: the resulting achievement of a lifetime dedicated to maritime duty, service, and ingenuity; it was as thought all of the lessons Gibbs had previously learned — about safety at sea, hull formation and design, propulsion systems, passenger accommodations, etc. — would come to be applied within the canvas of the SS United States project; such an evolutionary ship proved revolutionary: on her first crossing each way in 1952, the Big U won the Blue Riband8 for her nation: an honor that she will (likely) never relinquish. Until the SS United States reclaimed the award, an American ship had not garnered the award for an entire century: dozens of ships and numerous nations had won (and held) the Blue Riband since SS Arctic and SS Baltic had claimed it for the United States in 1852 and 1854, respectively. After the excitement of the Blue Riband, the Big U would go on to have a great and reliable, if unremarkable, career.

*Writing articles like these takes a lot of time and effort. The Great Conversation is committed to remaining a free publication that is accessible to all. If you have enjoyed this article, please consider making a one-time contribution here.

Born in a Waning Age

The Big U’s proprietor — i.e. the private, but publicly subsidized, United States Lines — operated her in tandem with running mate, SS America. Of note to readers at the present moment: the SS America — America’s original flagship — also met an inglorious, ignominious end: being broken to pieces on the rocks off an island in the Canary Islands, after she broke loose during a failed towing attempt in 1994; it would seem that in the end, the ocean always wins, taking back from man, his momentary victories over nature and her multitudinous forces.

Contemporary critics of the United States’s preservation as a museum-ship frequently like to point out that because she came about at a time when the world was in transition, she is therefore (somehow) less important than ships like the Queen Mary. I am not sure I follow such a line of reasoning, as no ship has ever borne the name of the United States so proudly, boldly, or magnanimously; when it comes to machines purposed for transportation, no news (of war or incident) is usually good news: just ask Boeing as of late — or, more aptly, the defunct White Star Line, who amalgamated into Cunard, never having fully recovered its reputation from titanic infamy.

And to such an end of safe, effectual transport — which is the only true “end” for modes of transportation — the United States (with credit owed to the dutiful service of her captains and crew), nobly performed the duties with which she was tasked: it is not her fault that the jet would come to supersede the ocean liner; nor is it her fault that she was too late for WWII (and that she had the pleasure of operating at a leisured time, of tense and tenuous, mid-century peace, that ended up holding).

Further, owing to the military interest in the ship, the technological aspects of the ship’s design were kept a closely-guarded, classified state secret until after her service life had concluded.9 As a result of such a partnership between public and private interests, details on the SS United States propulsion and other electro-mechanical systems remained scant for a long while — at least compared to other contemporary liners. I mention all of this to acknowledge that such details being classified has tremendously hindered efforts to repurpose or conserve the ship; until at least 1978, the United States government — under the auspices of the United States Maritime Administration — expressly forbade the ship being sold to a foreign power or agent (or the operation of the ship under a foreign flag), which was long enough to thwart a 1976 attempt to acquire and repurpose the ship by Norwegian Cruise Lines, who ultimately chose to purchase the similar SS France instead — rebranding her the SS Norway.

A 990 Ft. Picture: What it Means to Neglect the Preservation of the Past

Seeing such great ships — once icons of their respective nations, who received such triumphant fanfare by millions of doting spectators upon arrival in New York Harbor — be jet-tisoned to an early grave (as was the case with the SS United States in 1969), neatly demonstrates how short-sighted and ephemeral most material pursuits are in actuality — no matter how noble and significant they may have seemed at the time; and yet, it is far more difficult to maintain a necessary understanding and appreciation of the past without such non-fungible links to our common cultural past, from which we have emanated and been given life.

But in all this we should note that great people and great things are created with “meraki”10 by people; such material things, therefore, deserve to be remembered at least — preserved if (and when) possible. I am not sure where this leaves the Big U, but ultimately: material things matter because the people who built them mattered — their lives, their dignity, their work, their loving creations. The former is not merely to state that if we want to matter to the people of the future — which for many good, contemporary concerns, they too may forsake and cast off our many good (and wayward) works — that we ought care for (and thus preserve) certain tangible achievements of the past, but also to acknowledge that doing so is part of our uniquely human duty, to link the past to the present through synthesis of artifacts and narrative.

To not do so, is to shirk our duty to link the past to the present, and the present to the future. “Legacy” is a strange concept and one that is mostly absent from our present culture, which almost always tends to forsake the old for the new — the change endemic in such an incessant “religion of progress,” fails to preserve even the “good” parts of the past. Everywhere in America over the past century, our history — and therefore the many good, beautiful, and ingenious creations of our ancestors — has been forsaken through a process of razing and remaking, in a new sterile (and sprawling suburban) conception. If we hope to preserve our country, we must preserve tangible links to our past — particularly ones as triumphant and beneficent as the SS United States: a great icon and symbol of America at her best; she presents in plain sight, what we could — as a nation — once more aspire towards.

End Game: What All of This Means for Us — I.e. for Our Material Creations and Pursuits to Turn Out to be Meaningless in the End

But that is only one side of the token: for in the end, I don’t think a simple return to the soil of the land and sand of the seafloor is a satisfactory aim for our species. And so, in light of such wanton disregard for the great material achievements of organized industry in the past, I must (rhetorically) ask Gibbs and others: was it worth it? Or, should we all aim to spend our time pursuing things that may end up to be more everlasting than the creation of the greatest (American) passenger ship of all time? — on whose hull plates and turbines, once rested the hopes and aspirations of a mighty nation in its Belle Epoque of cultural cohesion, economic prosperity, and military and industrial might.

Such discussion raise a larger notion about the endless march of technological progress and its propensity to trample the people who make such a ceaseless pursuit possible — while later callously and flippantly, discarding their loving creations as abject scrap material: only fit to be used as an artificial reef. Disregard of the significance of past machines and edifices has become so rampant, that once it is deemed that “usefulness” has been fully expunged — or a “more efficient” alternative exists — we are told that what was once revolutionary, now has no practical use, meaning it should be destroyed or otherwise discarded: such a principle, I think, defines the disposable nature of American “consumer culture.” Ceaseless “innovation” for its own sake eventuates in swift discard — and with such swiftness, people in our society (who spend their lives building such machines) often live to see the death of the great feat they had personally helped achieve: such a phenomenon must be incredibly disheartening and destabilizing to those people. Why don’t we, as Americans, attempt to create lasting, permanent things anymore?

That, I think, is the lesson that of the SS United States: i.e. that when something great and momentous is pursued and created by humans, no one ever asks how it will end; but all things, peoples, and nations must end: such entropy is a “first principle” of the universe; and seeing such vacuous values — i.e. that of a nation wholly dedicated to short-sighted material pursuits (as in the case of America) — laid bare by the tangible demise of an achievement I personally — for many reasons — value greatly, is yet another reminder that life is short and civilization is incredibly transient and frail. Time is the true currency of life and most real history is never recorded: how we spend the time in our individual lives is, therefore, what matters most. And while I would nonetheless love to see the Big U preserved for posterity, perhaps our collective achievements are not so great as we have come to think: our successors never seem to think so, at least.

There is Still Time to be Hopeful: She is Not Yet Lost

To survive and remain whole (rather than loosely-affiliated fragments), a nation needs a culture to be proud of and inspired by: to aspire to great heights, one must be inspired. To have a functioning culture, thusly requires a mythology; and what does the SS United States represent for us, but a tangible, mythological link (however momentary) to the past? — a link which when severed, is seldom if ever, duly duplicated: it is for these reasons the Big U — our ship — is not only indispensable, but irreplaceable: the social, political, and economic factors that made the achievement of her creation possible will, in all likelihood, never coalesce together again. Ergo once she is gone, she is gone — and all others of her kind (excepting the Queen Mary) are already gone. To sink her and not save her is to forsake our duty to our collective cultural myth — our ethos as a nation, on which our survival and flourishing hinge.

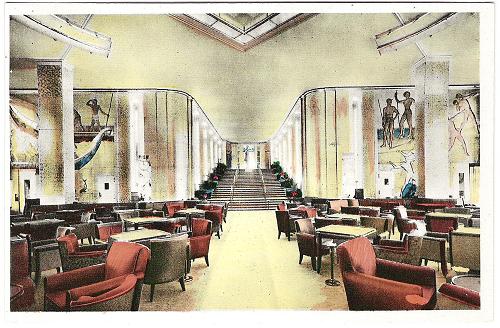

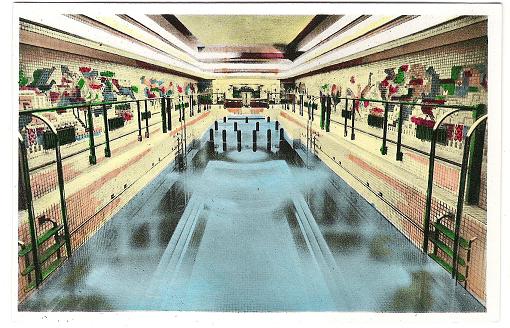

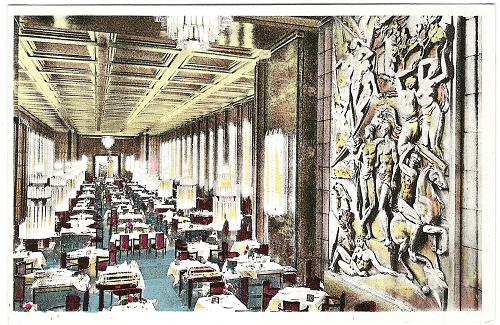

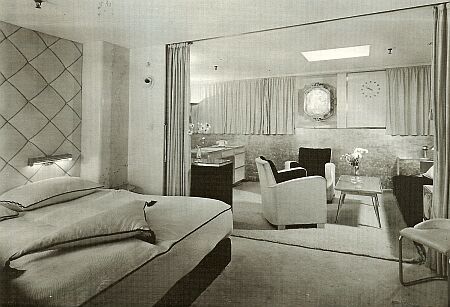

The Big U’s interior spaces in her heyday.

But nonetheless, what happens next — in the coming weeks and months — will come to define us and our age: will we dispense with a ship once deemed indispensable and vital to American predominance and flourishing? — a ship that is, perhaps, the greatest remaining icon of post-war, mid-century Americana at her best and strongest. Or, will we do right by our ancestors and save their momentous ship? — one that so many proudly toiled and served on — which has become our “burden” to either persevere or dispense with. To me, the choice is obvious, but this is a question of pecuniary means and an often short-sighted public will; I am hopeful, however: as the tide of public opinion seems to be changing. For instance, a coalition in New York has formed and appears to be taking legal action.

What will you do to help save the SS United States before it is truly too late?

*Writing articles like these takes a lot of time and effort. The Great Conversation is committed to remaining a free publication that is accessible to all. If you liked this article, please consider making a one-time contribution here.

Endnotes

1 I say six decades of “superliners” because I am considering the RMS Mauritania and Lusitania the first of their breed of high-performance, steam-turbine driven large multi-purpose passenger and cargo ship. These years spanned roughly 1907–1969 — beginning with the aforementioned Cunard greyhounds, and ending with the decommissioning of the RMS Queen Mary (1967), RMS Queen Elizabeth (1968), and SS United States (1969).

While the SS France remained in transatlantic passenger service until 1974 — and Cunard’s Queen Elizabeth 2 and Queen Mary 2, respectively, have conducted seasonal crossings into the present — the truth is passenger numbers dwindled to a trickle as the 1960s ensued, making such large passenger ships obsolete and financially untenable.

2 A ship of state is a large seagoing ocean liner capable of being converted to troop or auxiliary military use in a time of war. Such ships were owned and operated by private companies, but featured building costs that were subsidized by national governments; as a result, the government reserved the right to requisition ships of state in a time of need. In practice, such a process primarily occurred during total and global war: i.e. WWI and WWII.

3 The SS United States’s christening was said to be the first ship christening broadcast on live television, adding to her list of “firsts.”

4 There were many historical variations of hybrid-propulsion ship, many of which had a “composite” structure consisting of a wood hull-planks overlaid a wrought iron structural frame.

5 The SS America was the SS United States’s “running mate”; she was a smaller and slower pre-war ship, but featured rich and beautiful “Art Deco” interiors, similar compartmentalization against fire and flooding (as the Big U), and an overall uncanny resemblance. Designed by the William Gibbs and co., she served a very long and illustrious career that spanned over forty years.

6 Such a disaster occurred due to good, old-fashioned Yankee carelessness while operating cutting torches below decks; and owing to a hierarchical American bureaucratic structure and chain of command that was slow to react, the Normandie proceeded to overturn in her slip from the weight of the water from firefighters; such a capsize was able to occur because the ship’s lower levels were not intentionally flooded — as was advised by her chief designer, who was in New York at the time and pleaded with officials earnestly to do so — to allow the ship to fill with water evenly to rest on the shallow sea bottom, which would have enabled her to be refloated and salvaged afterwards. Due to wartime priorities, she was left there for years — ruining the great lady of the sea in the process.

7 The SS United States features an all-aluminum superstructure, which when combined with her roughly 248,000 HP power plant, made her — pound for pound — the lightest and fastest passenger ship ever designed and executed. At the time of construction, the SS United States featured more aluminum than any other object ever made by men.

8 The Blue Riband of the Atlantic was an unofficial, but culturally significant, award given to the fastest passenger liner to cross the Atlantic — both eastbound towards Southhampton and westbound to New York City.

9 This is owing in large part to the fact that the United States would prove useful as test-bed for new boiler and steam turbine technologies, later employed on the forthcoming Forrestal class of fleet aircraft carriers — that could reach similar blistering speeds of up to 34 knots — turning out to be the fastest, but penultimate, class of conventional, fuel-oil burning carriers commissioned by the US Navy (who now relies on nuclear power for its fleet carriers and submarines).

10 A Greek concept to signify a loving, fully-invested act of creation.

Comments